Saturday, August 23, 2008

Portuguese India, the Politics of Print and a ambiguous Modernity

Saturday, July 05, 2008

The Third Culture: Some aspects of the Indo-Portuguese Cultural Encounter

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Songs of the Survivors - A Book Review

Monday, January 21, 2008

Goa books, best-sellers

* GOA: The Land and the People. Olivinho JF Gomes, National Book Trust Rs. 110 * 100 Goan Experiences Pantaleao Fernandes The World Publications Rs. 395 * GOA Romesh Bhandari Roli Books Pvt. Ltd. Rs. 225 * A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of Goa P. Killips Orient Longman Rs. 195 * Goa: A select Compilation on Goa's Genesis Luis De Assis Correia Maureen Publishers Pvt. Ltd. Rs. 395 * Goa's Struggle for Freedom Dr. P. P. Shirodkar Sulabha P. Shirodkar Rs. 395 * Farar Far- Local Resistance to Colonial Hegemony in Goa 1510-1912 Dr Pratima Kamat Institute Menezes Braganza Rs 200 * Goa Indica: A Critical Portrait of Postcolonial Goa Arun Sinha Bibliophile South Asia in associate with Promilla & Co., Publishers Rs. 495 * Goa With Love Mario Miranda M & M Associates Rs. 350 * House of Goa Gerard Da Cunha Architecture Autonomous Rs 1900

Career books

Publishing travails

Online text

Learn Konkani

Memoirs ... of a voice from the airwaves

Friday, January 19, 2007

Remembering the Fall of Portuguese India in 1961

Francisco Cabral Couto, O Fim do Estado Português da Índia, Lisboa, Tribuna, s.d, ISBN.10:972-8799-53-5, pp. 136.

Priced at € 21.60 by FNAC in Lisbon, this hard cover coffee-table publication is perhaps the latest addition to the surprisingly rich and often controversial historiography about the end of the Portuguese colonial rule in India.

The author, now a retired general, was a young 26-old fresher from Military Academy when he arrived in Goa on 27 March 1961 and was posted at the Afonso de Albuquerque military camp in the village of Navelim, with command over 47 «caçadores» (hunters) with responsibility for the defence of Borim bridge, Paroda canal, river Sal and Anjidiv island. Within months the reinforcements made a total of 158, including many youngsters with little military training.

They were mostly involved in reconnaissance missions to ward off terrorist attacks. Describes the lack of basic conditions for any sort of defence in any terms of strategic or military means at disposal. The camp headquarters at Navelim had a generator that did not work, and depended upon the use of kerosene lamps and stoves.

With the exception of the delicious mangoes and abundant supply of bananas, classifies the food resources in Goa as of poor quality. There were canned supplies of quality food and drinks from UK and Holland, but few could afford them. The author admits that he did not stay in Goa long enough to take the pulse of the civil society, but remained with the impression that most Goans favoured autonomy or integration with India. Felt that the Portuguese presence was tolerated and even respected, but not much loved: «Quanto aos portugueses, é importante dizê-lo, pareceu-me que eram, dum mode geral, respeitados, bem tolerados, mas não amados, a não ser por aqueles que com eles tinham fortes laços familiares» (pp. 20-21).

While the acts of terrorism in Goa were multiplying, the Portuguese authorities were curiously encouraging the families of the men posted in Goa to join them, giving a false impression that all was well in Portuguese India. The author had his first son born on the eve of his departure to India. His wife and 5-month old son arrived by the first flight of TAIP in July.

While reporting about the relics of the Portuguese naval force in Goa, the author refers to a curious incident in September 1963 when Salazar ordered the ground batteries at the fort of Almada in Portugal to fire upon the cruiser Afonso de Albuquerque for having joined the republican forces in the Spanish civil war! Hence, ironically, the Indians were the not the first ones to do fire upon this war vessels. The author does not fail to report that the Commander of the warship was gravely hurt in the Vijay Operation, but his life was saved by the Indian military medics who treated him on shore in the Naval Club at Caranzalem.

The author reveals that in an emergency defence planning meet in September 1961 he had opposed the «Plano Sentinela» that was approved by the home government for resistance to Indian attack, suggesting that the defence should concentrate in the capital island, and not in Mormugão. Confesses that he was asked to drop his objections and withdraw his suggestions. Reveals another «Plano de Barragens» that has found no mention in earlier publications known to me. It complemented the «Plano Sentinela». It was meant to demolish the vital bridge links to delay the advance of the enemy forces. The same plan envisaged also mining of the main roadways and beach approaches. But lack of mines did not make it viable.

We have a fairly detailed description of the events at Anjidiv on 23-24 November, when the Portuguese forces stationed there fired upon the passenger vessel Sabarmati passing between the island and Kochi harbour, causing some deaths. The Portuguese forces were convinced that Indians were planning to disembark in the island. The Indian press was agog with news on 25 November and provoked a rapid escalation of diplomatic and military tension. The Portuguese official sent from Goa to investigate the case reported that the soldier manning the gun had fired upon the ship alleging that it was within the Portuguese territorial waters on 17 November and had kept his action unreported.

On December 9 the vessel India arrived from Timor on its way to Lisbon. With capacity for 380 passengers, it left on 12 December carrying 700, despite a telegram received from Lisbon ordering the Governor General to not permit any families to embark in the ship. The Governor General ignored the order. Allowed all who wanted to leave to embark and the passengers were fitted even into the bath rooms during night time.

It arrived in Lisbon on the last day of the year. The most valuable and original contribution of this book are the very personal experiences of the author after his detention by the invading forces. Such details as we read in pp. 103-116 constitute the value that this kind of personal memoirs can bring to historiography, despite and precisely because of their questionable nature of subjective version. Every personal version counts and is important for the re-construction of an «objective» history.

Francisco Cabral Couto describes the humiliation he felt when the Indian troops forced them to break up their weapons and arrange them in mounds. He got a gun-handle knock on his knuckles when tried to play dumb. Greater humiliation awaited him when his group was taken to the Navelim camp where he had been in command. Now he and his colleagues had to sleep on cement floor, dig trenches to serve as open-air latrines, and had to go make do with a jar of water that was supplied by tanks of Margão Muncipality.

Confesses that this shortage was caused by the Portuguese themselves by destroying the bridges and other supply routes. Remembers how the Christmas was celebrated with some dry biscuits that meant much in the context. Most interesting is the fact that among the guards, soldiers of Indian army he recognized three who had served in Goa as train TC, another as Longuinhos bar servant and a third who would be seating as a beggar under a banyan tree. After all, they seem to have been serving the Indian spy system, and nobody had sensed it.

The Navelim internees where shifted to the Ponda camp in mid January 1962, where the Alfa Detenues Camp was much better organized. Describes how a few soldiers tried to escape, provoking a serious incident when the some of the Portuguese officials were called upon to admit lack of responsibility and were threatened with death by shooting. The timely intervention of a Jesuit military chaplain ended it all without any tragic consequences. The author admits that he and his Portuguese colleagues admired the discipline of the Indian army, which was equally just in punishing its own members who failed to comply with rules.

Describes how he left Goa by air to Karachi on May 8 and embarked on 9th for Lisbon aboard Vera Cruz. On arrival in Lisbon 11 days later, they were taken away early in the dark of night under police escort and without access to the families that awaited them. In the following months all were subject to unending questionings, until on 22 March 1963 a list was published of those who were subject to punishment of some kind, and many were dismissed from service without right for self-justification.

The book ends by admission that Salazar failed to calculate well the international support, but that also the Indian invasion proved the Portuguese capacity to resist subversion. This conclusion appears to be a non sequitur after the author admits that Nehru has shown great patience for nearly two decades, and implying that no one can be tested indefinitely, as did the Portuguese diplomatic intransigence. Perhaps the photo chosen to be included in the book reveals author’s bias and provides an answer? Is the photo meant to illustrate Nehru’s intimacy with the Mountbatten couple, or does it insinuate anything else?

Teotonio R. de Souza

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Forum/1503/teo_publ.html

Francisco Cabral Couto, O Fim do Estado Português da Índia, Lisboa, Tribuna, s.d, ISBN.10:972-8799-53-5, pp. 136.

Priced at € 21.60 by FNAC in Lisbon, this hard cover coffee-table publication is perhaps the latest addition to the surprisingly rich and often controversial historiography about the end of the Portuguese colonial rule in India.

The author, now a retired general, was a young 26-old fresher from Military Academy when he arrived in Goa on 27 March 1961 and was posted at the Afonso de Albuquerque military camp in the village of Navelim, with command over 47 «caçadores» (hunters) with responsibility for the defence of Borim bridge, Paroda canal, river Sal and Anjidiv island. Within months the reinforcements made a total of 158, including many youngsters with little military training.

They were mostly involved in reconnaissance missions to ward off terrorist attacks. Describes the lack of basic conditions for any sort of defence in any terms of strategic or military means at disposal. The camp headquarters at Navelim had a generator that did not work, and depended upon the use of kerosene lamps and stoves.

With the exception of the delicious mangoes and abundant supply of bananas, classifies the food resources in Goa as of poor quality. There were canned supplies of quality food and drinks from UK and Holland, but few could afford them. The author admits that he did not stay in Goa long enough to take the pulse of the civil society, but remained with the impression that most Goans favoured autonomy or integration with India. Felt that the Portuguese presence was tolerated and even respected, but not much loved: «Quanto aos portugueses, é importante dizê-lo, pareceu-me que eram, dum mode geral, respeitados, bem tolerados, mas não amados, a não ser por aqueles que com eles tinham fortes laços familiares» (pp. 20-21).

While the acts of terrorism in Goa were multiplying, the Portuguese authorities were curiously encouraging the families of the men posted in Goa to join them, giving a false impression that all was well in Portuguese India. The author had his first son born on the eve of his departure to India. His wife and 5-month old son arrived by the first flight of TAIP in July.

While reporting about the relics of the Portuguese naval force in Goa, the author refers to a curious incident in September 1963 when Salazar ordered the ground batteries at the fort of Almada in Portugal to fire upon the cruiser Afonso de Albuquerque for having joined the republican forces in the Spanish civil war! Hence, ironically, the Indians were the not the first ones to do fire upon this war vessels. The author does not fail to report that the Commander of the warship was gravely hurt in the Vijay Operation, but his life was saved by the Indian military medics who treated him on shore in the Naval Club at Caranzalem.

The author reveals that in an emergency defence planning meet in September 1961 he had opposed the «Plano Sentinela» that was approved by the home government for resistance to Indian attack, suggesting that the defence should concentrate in the capital island, and not in Mormugão. Confesses that he was asked to drop his objections and withdraw his suggestions. Reveals another «Plano de Barragens» that has found no mention in earlier publications known to me. It complemented the «Plano Sentinela». It was meant to demolish the vital bridge links to delay the advance of the enemy forces. The same plan envisaged also mining of the main roadways and beach approaches. But lack of mines did not make it viable.

We have a fairly detailed description of the events at Anjidiv on 23-24 November, when the Portuguese forces stationed there fired upon the passenger vessel Sabarmati passing between the island and Kochi harbour, causing some deaths. The Portuguese forces were convinced that Indians were planning to disembark in the island. The Indian press was agog with news on 25 November and provoked a rapid escalation of diplomatic and military tension. The Portuguese official sent from Goa to investigate the case reported that the soldier manning the gun had fired upon the ship alleging that it was within the Portuguese territorial waters on 17 November and had kept his action unreported.

On December 9 the vessel India arrived from Timor on its way to Lisbon. With capacity for 380 passengers, it left on 12 December carrying 700, despite a telegram received from Lisbon ordering the Governor General to not permit any families to embark in the ship. The Governor General ignored the order. Allowed all who wanted to leave to embark and the passengers were fitted even into the bath rooms during night time.

It arrived in Lisbon on the last day of the year. The most valuable and original contribution of this book are the very personal experiences of the author after his detention by the invading forces. Such details as we read in pp. 103-116 constitute the value that this kind of personal memoirs can bring to historiography, despite and precisely because of their questionable nature of subjective version. Every personal version counts and is important for the re-construction of an «objective» history.

Francisco Cabral Couto describes the humiliation he felt when the Indian troops forced them to break up their weapons and arrange them in mounds. He got a gun-handle knock on his knuckles when tried to play dumb. Greater humiliation awaited him when his group was taken to the Navelim camp where he had been in command. Now he and his colleagues had to sleep on cement floor, dig trenches to serve as open-air latrines, and had to go make do with a jar of water that was supplied by tanks of Margão Muncipality.

Confesses that this shortage was caused by the Portuguese themselves by destroying the bridges and other supply routes. Remembers how the Christmas was celebrated with some dry biscuits that meant much in the context. Most interesting is the fact that among the guards, soldiers of Indian army he recognized three who had served in Goa as train TC, another as Longuinhos bar servant and a third who would be seating as a beggar under a banyan tree. After all, they seem to have been serving the Indian spy system, and nobody had sensed it.

The Navelim internees where shifted to the Ponda camp in mid January 1962, where the Alfa Detenues Camp was much better organized. Describes how a few soldiers tried to escape, provoking a serious incident when the some of the Portuguese officials were called upon to admit lack of responsibility and were threatened with death by shooting. The timely intervention of a Jesuit military chaplain ended it all without any tragic consequences. The author admits that he and his Portuguese colleagues admired the discipline of the Indian army, which was equally just in punishing its own members who failed to comply with rules.

Describes how he left Goa by air to Karachi on May 8 and embarked on 9th for Lisbon aboard Vera Cruz. On arrival in Lisbon 11 days later, they were taken away early in the dark of night under police escort and without access to the families that awaited them. In the following months all were subject to unending questionings, until on 22 March 1963 a list was published of those who were subject to punishment of some kind, and many were dismissed from service without right for self-justification.

The book ends by admission that Salazar failed to calculate well the international support, but that also the Indian invasion proved the Portuguese capacity to resist subversion. This conclusion appears to be a non sequitur after the author admits that Nehru has shown great patience for nearly two decades, and implying that no one can be tested indefinitely, as did the Portuguese diplomatic intransigence. Perhaps the photo chosen to be included in the book reveals author’s bias and provides an answer? Is the photo meant to illustrate Nehru’s intimacy with the Mountbatten couple, or does it insinuate anything else?

Teotonio R. de Souza

http://www.geocities.com/Athens/Forum/1503/teo_publ.html

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Goan women... and the written word

Am a regular reader of your blogs and posts on various goa-linked forums.In response to an old query posted by you on Goacom [I guess he means Goanet.org --FN] -- on notification of new goan authors, below are two recent releases, both by Goans, and both based in part on fictional villages in Goa

- Nandita da Cunha.Novel: The Magic of Maya. Info at http://nanditadacunha.blogspot

.com - Sonia Faleiro,Novel: The Girl,Info at http://soniafaleiro.blogspot

.com

There are also short stories (again based on Goa) by Nisha da Cunha, and a non fictional account by Maria Aurora Couto but I do not have a link to that. I have read and enjoyed all these books, especially the short stories by Nisha (the only non-Goan in the list above!) ... most of which however have a darker side to them. You could update your database/ reviews section with any of these if you like. Do let me know if this is of any use.

Thanks so much Aloke. Your post (though I knew these names, fiction doesn't interest me as much as non-fiction....) suddenly drew my attention to the fact that in our, patriarchal, Goan society, women writers are fairly well well represented. As it happens, I kept up till late last night, reading some chapters of Imelda Dias' How Long Is Forever? An Autobiography of a Woman Ahead of her Times.

technorati tags:goa, womenwriters, feedback

Blogged with Flock

Sunday, January 14, 2007

Looking at Goa's heritage... in its various shapes

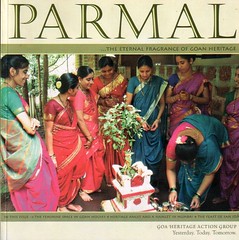

One of my favourite Goa-related journals was released the other day. Parmal. It's latest issue has on its cover this photo showing traditionally-attired Goan Hindu young women at a festive celebration. Parmal is published by the Goa Heritage Action Group, and calls itself "an annual publication brought to you by the GHAG, an NGO (non-governmental organisation) based in Goa dedicated to the preservation, protection and conservation of Goa's natural, cultural and man-made heritage".

Prava Rai is Parmal's editor. She does a great job of it. It fits in with my view that some of the so-called "non-Goans" (and returned expats) are among those who are contributing the most significantly to Goan society today. The simplistic barrage against them notwithstanding.

Prava says in the editorial: "The danger of equating heritage with identity fosters untenable claims to the bones, belongings, riddles and the refuse of every forbear into the mists of time: ipossible claims in the face of historical reality."

My view of the GHAG is that it tends to be a bit elitist in nature. Sometimes. This places it somewhat closer-to-comfort to the Establishment than it perhaps should be, and blocks it from taking more strong, campaign-oriented stands. But, on the positive side, it helps them get an official hearing. Sometimes. Their approach also means they do a great job to generate content that has much relevance to the debate about Goa.

This issue contains articles, among others, focussed on the mother goddess cult (by Portuguese studies specialist Ana Paula Lopes da Silva Damas Fita), the feminine space in Goan houses (architecture writer Heta Pandit), sacred groves (field ecologist Nirmal Kulkarni), the Fontainhas Festival of the Arts (artist and journalist Deviprasad C Rao), Goan residential architecture (Sanskrit scholar and prof of theology Jose Pereira), the parish churches of Goa (civil engineer-turned-author and Goalogist Jose Lourenco), the legacy of the house of Menezes Braganca (sociologist Nishtha Desai), forgetting Pio Gama Pinto (by SOAS-London educated researcher Rochelle Pinto), and Mumbai-based freelance writer Veena Gomes-Patwardhan's The Stars of Yesterday (from the Konkani stage).

If you'll allow me to brag a little (which is what one is usually doing!), we managed to point to the interesting ideas of some writers by having them e-published on Goanet Reader... and Parmal/Prava did a good job of following up. Of course, we should be doing far, far more on this front....

technorati tags:goa, heritage, parmal, ghag, goaheritageactiongroup, books, reviews

Blogged with Flock

Saturday, July 08, 2006

Sunday, January 22, 2006

BOOK REVIEW: Secrets behind church facades (by Melvyn Misquita)

Secrets behind church facades

BY MELVYN MISQUITA [Herald] melvyn at misquita.net

What do mermaids, a two-headed eagle, lions, the mythical Cyclops and a boat have in common? Believe it or not, they all grace the façades of parishes churches in Goa.

To be honest, a casual spectator may find façades of the 158-odd parish churches in Goa nothing more than repetitive white-washed multi-storeyed structures that deserved nothing more than a cursory glance.

That is, until they lay their hands on the recently published book "The Parish Churches of Goa", a study of façade architecture by Jose Lourenco along with photographs by Pantaleao Fernandes.

The 201-page book is packed with exhaustive, yet fascinating, information and pictures on façades of parish churches, right from Agassaim to Veroda and even includes a map of Goa identifying the parish churches for the curious traveller. The book, however, does not include facades of non-parish churches (churches at Old Goa).

The authors begin by briefly describing the various architectural influences of the west and east on church façades in Goa.

The early façades, according to the authors, were the 'peaked gable' façades, relatively unsophisticated late Portuguese Renaissance style, as can be seen in the parish churches such as St Peter (Sao Pedro) and St Lawrence (Agasaim).

The 'Cupoliform' façades, considered a Goan innovation, can be seen in churches such as Our Lady of Immaculate Conception (Moira) and St Cajetan (Assagao).

Other façades include the 'Pozzoan pediment' (such as Holy Spirit, Margao), 'Rococo' (such as St Jerome's Church, Mapusa), 'Templet' (such as Savour of the World church, Loutolim) and 'Neo-Gothic' (such as Our Lady church, Saligao).

A concise description of each parish in Goa is encompassed in a single page, which includes other interesting details such as a brief history of the parish, the feast of its patron (now you don’t have any excuse for missing out on parish feasts of your relatives), the elevation/ inception of the parish, the latest picture of the parish and architectural notes on the facade of the church.

While praising the rich architectural heritage of façades in the parishes churches of Goa, the authors seem pained over the recent unintentional 'distortions' to these façades, which, in their words, "have marred the elegant beauty of these edifices."

Some of these 'distortions' detailed in their book include the installation of metalor plastic sheets to protect doors, windows and belfry openings, concrete porches, back-lit signboards and 'blinded openings', the closure of the oculi (the opening that streams light into the church interiors).

The authors also express anguish over the recent trends to paint church facade in multicolours, a far cry from the "resplendent brilliance" of the white paint of yore, besides pointing to recent trends of introducing fluorescent or sodium vapour lamps on or around façades, aluminium windows and haphazard facade renovations.

A glossary and sketches containing the different elements of the church facade are also a useful addition in the book.

The book is certainly an eye-opener to those who will now admit that facades of churches are much more than repetitive white-washed multi-storeyed structures that deserved nothing more than a cursory glance.

While the book is strongly recommended for the fascinating stories that emerge out of church facades, there is, however, one drawkback -- its price.

Priced at Rs 495, the book is by no means cheap and could well elude the masses, who may miss out on the hidden secrets of church facades. (ENDS)

Monday, January 02, 2006

Sonia's book, The Girl

Sonia Faleiro <faleiro_s at yahoo.com> has just released a novel, The Girl, this month. More information is on her website www.soniafaleiro.com Looking forward to seeing the same...

Sunday, January 01, 2006

Amita Kanekar's A Spoke In The Wheel (HarperCollins, 2005)

Below are three reviews of a book by Amita Kanekar, a Mumbai-based writer whose roots are in Goa. -FN

The Hindu, May 1, 2005

The Buddha emerges a more rounded figure in this reinterpretation, says R. KRITHIKA

----- A Spoke In The Wheel: A Novel About The Buddha, Amita Kanekar, HarperCollins, Rs. 395. -----

THE traditional legend of Buddha's renunciation and search for enlightenment is, in many ways, unsatisfactory. Could one be as divorced from the reality of his/ her times as the legend implied? Also the characters seem unreal cardboard cutouts rather than real live people, who felt, loved, lived and hated especially when compared with extant literary sources on social life of this period in Indian history.

Good use of history

Against this background, Amita Kanekar's A Spoke in the Wheel is interesting reading. Described as historical fiction, the book draws from Indian history to such good effect that one can't help wondering if things actually did happen this way. The period of the Buddha was one of great philosophical ferment. There were six main schools of thought, the Vedic ritualistic tradition was under attack and people were beginning to look at alternate schools of thought. Both politically and socially too, it was a time of changes. Republicanism had come to the fore.

The book moves at two levels. A monk, Upali, (who lives in Asoka's times) is writing the story of Buddha's life. Upali has lived through the Kalinga War and is not quite sure about the reasons for Asoka's conversion is it a true inner change or is it politically motivated? Upali's story has raised hackles in the establishment since he avoids the traditional rendering. His Buddha is an outsider in his own society, racked by doubts and finding something lacking in the political and socio-religious structure of his times. But, initially at least, Upali has the support of the emperor.

A modern reader might find Upali's Buddha a more rounded figure than the over-protected prince of mythology. The reader is drawn to the character as his doubts and worries do have a contemporary resonance. But one can also understand the horrified reactions of the community of monks. After building up the greatness of Buddha, to have him portrayed as a nave, self-doubting individual out of sync with the socio-political environment can be damaging.

Dismantling legends

Another interesting aspect of the book is the dismantling of each legend associated with the Buddha. Beginning with his birth right down to his renunciation, Kanekar systematically demolishes the otherworldly gloss. The touch I liked best was the handling of the charioteer Channa when he brings the news of Buddha's renunciation home. Our lovely legends are silent in this. But Kanekar has Channa thrashed and thrown in jail till it is proved that Siddhartha was alive. More like those times and these too.

Life in the Magadhan empire is also portrayed with an eye to historical accuracy. Quotes from Asokan edicts which we knew of as history but couldn't really relate to now come alive with a new imagery. The schism within Buddhism which Asoka tries to bridge with the Buddhist Council is portrayed through the conversation of the monks. Political intrigue, a given constant in all times, reaches through insidiously into the Sangha - one of the elders is a spy for the emperor, another monk is murdered for his political affiliations.

Same old stories

The other interesting issue is the expansion of so-called "civilisation" and the effect it has on tribals and other forest-dwelling people. The young Siddhartha is troubled by the treatment and enslavement of defeated tribals. By the time of Asoka, the expansion of the Magadhan kingdom sees the forest dwellers fighting a losing battle to retain their way of life. One quote brings the reader slap up against the tribal agitations in today's world and the conflict between civilisation-development and the traditional cultures "Everything in the forest is not the same ... . Magadh has this way of demeaning the forests - using them, plundering them, destroying them and ignoring the richness, the layers, the differences, the thousands of thousands of differences." Not much seems to have changed in the years that have passed since then.

Kanekar's language is forceful and direct. Vividly drawn word pictures bring old textbooks to life. Upali is a figure who draws and holds the reader's interest. His stubborn refusal to accept the legends as sacred, his championing of the communities, his doubts over the king's reasons for conversion and promotion of Buddhism ... This is a book that will be of interest to anyone interested in philosophy in general and Buddhism in particular.

-----

Revealing the real Buddha by S A Karthik, The Deccan Herald, May 29, 2005

New Delhi, India -- The book is an attempt to strip away fanciful stories surrounding the Buddha and reveal him as an ordinary man who had an extraordinary approach to his problems.

In his Buddhacharita, Asvaghosha describes in majestic verse the unnatural splendour of the Buddhas birth: as Indra, the chief of the gods holds the newborn in his hands, two streams of the purest water from the heavens fall on the baby together with mandaara flowers. The baby then utters words of majesty and meaning: I am born for the benefit of this world. This is my last birth on this earth.

Amita Kanekar's debut novel, A Spoke in the Wheel is an attempt to strip away layer by layer such fanciful stories surrounding the Buddha and reveal him as an ordinary man who had an extraordinary approach to his problems.

At her hands the Buddhas story emerges plainer but more than makes up for that by offering a wealth of alternate, rational explanations that challenge blind belief in legends that were formulated largely to serve the selfish interests of particular clans, kings, and communities.

The novel has an interesting structure. It begins with the story of Upali, a monk in the Maheshwar monastery on the Narmada. He begins rewriting the life of the Buddha as he sees contradictions in the Suttas. The reader changes lanes every alternate chapter, from the story of Upali set in 256 BCE during the emperor Ashokas reign to the story of the Buddha three hundred years earlier as retold by Upali.

In his reconstruction Upali adopts what is a blasphemous approach in the eyes of the leaders of the Buddhist sanghas. He portrays the Buddha as an ordinary prince, apathetic to the kshatriyas vocation of war, abhorrent of their animal and human sacrifices, and sympathetic towards the plight of the slaves and other repressed peoples.

Upalis account is thus shorn of the legendary elements in Buddhas life - his divine birth, the reasons for him leaving home and hearth and his war with Maara the Tempter on the path to enlightenment.

Throughout the book Amita presents issues of ethics and socio-economic relationships that are relevant even today. The ruler-priest nexus that exploits the commoner, the ethical ambivalence of the merchant classes, the morality of war, the issues of displacement and rehabilitation (as in the case of the people of Kalinga after the war with Maghadha) and so on.

The book attempts to show that the Buddha went away in search of solutions to these earthly, mundane problems, not esoteric questions of existence. His Middle Way was his solution to the excesses of all types indulged by all classes. Did those who professed to follow the Way, including Asoka, actually do so or did they merely use it for their own ends?

The book has some stimulating answers to this question.

The narrative is rich in detail and every aspect of life in those ancient times stands out vividly before the reader. There is a glossary of terms at the end. Perhaps the only lacuna is the absence of notes that indicate the sources for Amitas inferences. At the end of the book we do not have the comfort of knowing what is supported by research and what is imaginatively concocted. But this is not to deny the books deserved place on our bookshelf.

A Spoke In The Wheel - A Novel About The Buddha; Amita Kanekar New Delhi: Harper Collins, 2005; pp 447, Rs 395

-----

Spetrum, The Tribune Sunday June 19,2005 Buddha demystified Arun Gaur

A Spoke in the Wheel by Amita Kanekar. Harper Collins, New Delhi. Pages 448. Rs 395

"Influenced by all!" said Mahanta. "Upalis Buddha is a confused fool parroting whatever was said around him!" "Thats not true," protested Upali. "Perhaps it is not deliberate," conceded Mahanta. "Perhaps it is only your stupidity." He turned to the others. "But just imagine, brothers, if everybody started this kind of imaginative interpretation, what will happen to the legacy so carefully protected this far? It will be torn apart, destroyed! Well be left with only interpretations, each one more adventurous than the last!"

Upali is a monk, a Chandala, a remnant of the Kalinga war, seething with hatred towards Ashoka. Ironically, he is supported by the king himself in his private enterprise of writing Buddhas biography. Only three centuries separate the Buddha and his biographer, but these are enough to mythologise him heavily.

Now the primary task, the self-appointed mission, of Upali is to demythologise the sage, deconstruct the associated fantasies of the Suttas and the Jatakas, and to place him firmly in the historical matrix. His fears are strong: "To make him a god is to make him ordinary. He will be one of thousandsthis is a land of gods. He will be swallowed up by myth and ritual. He might even become a sacrifice demander and a slavery-patron tomorrow, one who needs blood and flowers and incense and servants!" The biographer is irritated at the inimical stance of the fellow monks: "My understanding is simple... The Buddha was a very wise man, but a man." Harsha knows better: "Upali! The Buddha is already a godone story cant stop it."

How can Upali be free to create his own Buddha? Even Ashoka opines that time is not ready to receive his Buddha and directs him to deposit his manuscript with him. The post-modernist debate about the right to authorship is in question here.

Upali does not seem to nurse any ambition to become a renowned author and his enterprise seems to be a purely private affair, an exercise in self-contentment. Even then, society at largehis friend Harsha, Mogalliputta, who is the powerful thera of Pataliputra, and the courtiers of Ashokaholds the opinion that Upali is trying to appropriate a privileged position of an author. And that would not be granted to him. The interference of the state machinery cannot be countered by the individual flashes of genius. When the writing begins, a writer has to die. This option is not acceptable to Upali; for him, writing as well as the author has to die. Consequently, he throws his unfinished script into the fire and slumps into silence.

The abstract story of the recreation of the Buddha is embedded in a multi-layered phenomenon. The philosophic gaze of Upali takes into cognizance the spiritual, commercial, political, and artistic ingredients of the society surrounding him and somehow manages to persevere through this maze. Unwittingly, Upali also becomes a part of the intrigues of love and political assassinations.

Clearly, Kanekar has done a lot of research that this kind of novel writing demands. She examines diverse historic issues: Dhamma, jungle versus city, slavery-system, stature of a devadasi, national identities, crime and punishment. There are evocative descriptions of burgeoning cities like Kapilavastu, and Benares Ujjayinis "raucous noise" is sharply demarcated from Pataliputras "laughter from glamorous carriages."

As the novelist is a teacher of the history of architecture and comparative mythology, she comfortably deals with the details of a Yakshini on the stupa: "Her pose seemed modeled on a liana vine, her ridiculously generous curves on fruit-laden trees, but her expression? The amused challenge in her eyes" Still more important is the fact that this observation is not a dry piece of analytical realism; as it is conveyed through a monks eyes, it suggests an amorous hidden dimension of a spiritual being.

Here is an abstruse difficult-to-handle story that could easily have gone drab, but it goes to the credit of the writer that in spite of her being a debut-novelist, she has been able to keep it lively. It seems to be an important contribution to Indian historic fiction.

Tuesday, December 27, 2005

Dr Jose Pereira ... on the mando

Friday, December 23, 2005

Blood, nemesis and misreading quite what makes Goan society tick (book review)

BLOOD, NEMESIS AND MISREADING QUITE WHAT MAKES GOAN SOCIETY TICK

Being trapped in the immobility of their social structures, the Lusitanian supremacy did not matter to the downtrodden.

[A review by: Lino Leitao lino.leitao at sympatico.ca]

---------------------------- Blood & Nemesis by Ben Antao Goan Observer Private Limited Pages 318, Rs 250. Goa 2005. ----------------------------

Ben Antao's 'Blood and Nemesis' is a historical novel. In this novel, the author attempts to recapture Goa's freedom struggle from Portuguese colonial rule. In doing so, he gives us insights into Goan psyches of both the Hindus and Catholics -- the two main sectors of the Goan population.

In the very first chapter of the novel, we are introduced to Jovino Colaco, a young constable in Goa's colonial police force at Margao. Jovino's character is very vividly drawn, as if the author had known such a character personally; and many a Goan freedom fighter might have come across such a lout in those days of their struggle to free Goa from Salazar's tyranny.

Though Jovino is a bonehead with nothing much of substance, he is shrewd enough to use his position as a police constable to acquire money by graft, harassing the drivers of carreiras -- the busses of those colonial times. He has huge appetites for booze and sex; and of course, he likes card games, gambling with his friends. For him, dictatorship isn't ugly; he has a nose to sniff out freedom fighters. His boss, Gaspar Dias, a fearsome detective, likes him for that, and promotes him as his assistant. And Jovino, who spends more money than he earns, sees it as an opportunity to make a lot of cash to support his tainted lifestyle. He is happy; the promotion goes to his head.

Jovino's sexual exploits introduce us to the Devdasi cult at Mardol. (Devadasi refers to temple-based prostitution, which existed till the early part of the 20th century. In Goa, a devdasi was also called Bhavin, or the one with devotion.)

Antao draws vibrant and titillating sexual performances; and Kamala, a family devdasi, a steady sexual partner of Jovino, an expert in innovative Kamasutra poses, knows to give and take sexual pleasures for herself. But at the same time, a reader might question, as I did, how this kind of degrading humiliation of the woman came to be sanctified in the Hindu religion?

June 18, 1946 is a historic date in Goa's history. On this day, Dr. Juliao Menezes, a Goan, and Dr. Rammanohar Lohia from what was then still British India lit the torch for civil liberties at Margao, defying the ban on the freedom of speech.

Santan Barreto, Jovino's nemesis, who was only eighteen years old then, was on the scene. Seeing Juliao and Lohia hustled into a Police jeep and driven to the Police station, had an effect on Santan's soul. It awakens to freedom.

Santan dreams going to college in Bombay, and participate in politics after India's independence. But his ambition is shattered when his father, a seaman, passes away on board the ship. Having no one else to support his ambition, he pursues his dream by becoming a 'social worker' -- a euphemism for joining the ranks of the unemployed. He runs errands to get in touch with the like-minded Hindus to bring in freedom and democracy. He could have easily got a job in the colonial administration; but being the zealous Goan patriot that he was, he couldn't compromise his principles. Nor do we see the like-minded Hindus offering him a job in their businesses that they owned.

Santan, an ardent idealist, whose soul burns fervently to usher in freedom and democracy to the Goans, has no scruples, whatsoever, to freeload on his mother's meager widow's pension. The poor woman, to make the ends meet, works her fingers to the bone laboring in the fields owned by others.

Santan, when released after Liberation from the Aguada jail doesn't rush back to his mother, the mother who had sacrificed her own needs and fed him on her paltry widow's pension, when he was a 'social worker'. Instead, we see him basking in 'hero worship', for a week at Vaicunto Prabhudesai's, a like-minded Hindu and a fellow political prisoner from Aguada jail.

The author portrays Santan, a freedom fighter, as an impulsive individual with no ability to control his anger when enraged. The reader will come across two incidents in the novel. One: a glass of pale amber liquid, which is Santan's urine, which he arrogantly demands Jovino drink. Why? If you read the novel, you’ll know the answer to it.

The other incident is when Santan snatches the revolver from Jovino's holster. These are impulsive and sporadic acts, not worthy of freedom fighters. Committed freedom fighters to the cause plan their acts carefully and execute them to get the desired results.

After Liberation, Santan and Vaicunto, their self-importance puffed up as Goa's liberators, rush to settle scores with Jovino. The author, in the end, renders a debauched Jovino, on his dying bed, as a better human being than those two vengeful liberators.

Subtly, the author exposes the conceitedness of Santan. One gets the impression that the author must have known such a character like Santan personally too, the way he draws out his hidden traits of his personality.

The plot though unfolds around these two main characters -- Jovino Colaco and Satan Barreto, other fascinating characters also pop up in the narrative, giving us the overall view of Goa's life in those colonial times under the dictatorship of Salazar.

Unsubstantiated historical perceptions are thrown into the story, sometimes they come through the mouth of the characters, or sometimes injected by the author himself. For example in pages 21 and 22, we read: "He (Gaspar Dias, Jovino's boss in Police Force) was convinced that the political sympathies of Goan Hindus definitely lay with India.... The younger generation of Hindus, if you cared to ask them, would say without hesitation that they wanted freedom from colonial rule; they wanted Goa to become a part of India. As for the Catholics, by and large, they tried to be good citizens...."

Gaspar Dias can be excused for such analysis of the Goan society of that time, he being a mestico, might not have ever assimilated the intricacies of Goan nationalism.

Again, in page 110 the author probes the thoughts in Santan's mind. The author writes, "...But he (Santan Barretto) was also aware that many Goan Catholics somehow had been brainwashed into thinking they were different from other Indians, that they were superior because of their Western ways of life."

We can make allowances for Santan too, and overlook his assumptions of this nature because the author has portrayed him as an impetuous freedom fighter; impetuous persons do not use their brain muscle but their emotions.

But it's historically fallacious inferences to assume that Goan Hindus were pro-Indian because of their religion, and that Goan Catholics were pro-Portuguese. The civil rights movement that was launched in 1946 was launched due to the endeavors of Dr. Juliao Menezes, who was a Goan and baptized Catholic, though he might have been an agnostic later on in his life.

In that civil rights movement, many Goan Catholics participated. To name only some important ones: Tristao da Cunha, baptized Catholic, though atheist later on; Berta de Menezes Braganca, baptized Catholic, perhaps atheist later on; Evagrio George, baptized Catholic; Aresenio Jaques, baptized Catholic; Critovao Furtado, baptized Catholic and many, many others.

Jose Inacio Candido de Loyola in Free Press Journal, Bombay, September 26, 1946 sums ups this movement in this fashion, "An attempt is being made in certain quarters to create among the Catholic section of the Goan population, the impression that Dr. Lohia's movement is directed against the Catholic religion. There is no truth whatsoever in this propaganda. This movement has nothing to do with any religion. It is a movement for all Goans."

Goans always struggled to break the fetters that bounded them, and the author brings to our mind at page 95 the Pinto's rebellion that took place in the summer of 1787. Weren't they Catholics?

Francisco Luis Gomes, in his maiden speech in the Portuguese Parliament (18th January 1861), spoke: "... but far better models are the sacred principles, which in a free government require that hundred of persons should not be deprived of their political rights, of rights through which they share in the creation or exercise the political powers, simply because they had the misfortune to be born in the overseas colonies." (Dr. Francisco Luis Gomes, 1829-1869, by Inacio P. Newman, Coina Publications Goa, 1969.)

And again, Menezes Braganca, when Acto Colonial was incorporated in the Political Constitution of Salazar's Dictatorship in 1930, repudiated the mentality of the Act, "Portuguese India does not renounce the right of all peoples to attain the fullness of their individuality to the point of constituting units capable of guiding their own destiny, for it is a birthright of its organic essence." (Menezes Braganza, Biographical Sketch)

At page 21, the author, while probing into the mind of Gaspar Dias, writes: "...(Gaspar Dias) knew that the older Hindu businessmen mostly paid lip service to the Portuguese administration in order to make a living -- and some became wealthy in the newly booming mining industry of iron and manganese ore."

The Goan Hindu businessmen, tradesmen and landlords weren't that naive; they knew which sides the winds were blowing. Goa was their personal fiefdom without an economic base. They understood that the economic power that they were holding would slip away from their hands if Goa integrated with free India, which had an economic foundation.

So, they organized a public assembly in Margao (O Heraldo, July 30, 1946), and petitioned Salazar's administration for autonomy for Estado da India. Jose Inacio de Loyola gave the presidential address. The others who spoke were Mrs. Krishnabai, the niece of 'Bairao' Dempo, Datta Naik, Francisco Furtado and Vicente Joao Figueiredo.

Laxmikanta Bembro, making various observations, proposed a committee of the following: Adv. Vicente Joao Figueiredo, Adv. Polibio Mascarenhas, Manganlal M. Kanji, Adv. Panduronga Mulgaocar, Adv. Francisco de Paul Ribeiro, Adv. Prisonio Furtado. Adv. Antonio Xavier Gomes Pereira, Bascora Desai, Dr. Jose Paulo Telles, Adv. Álvaro Furtado, Adv. Francisco Pinto Menezes, Adv Vinayka Sinai Coissoro, Adv Datta Phaldessai, Dr. Krishna Sanguri and Laxmikanta V.P. Bembro.

But their efforts did not bear any fruits. And again in 1961, Purushottam Kakodkar perused autonomy for Estado da India, with no success. Gaspar Dias, the character in Antao's novel, who is a fearsome detective and obviously based on Agente Casmiro Monteiro, seems to know nothing about Goan native nationalism.

"The Goan people, for all practical purposes, have been pulverized by these heinous acts of brutality; in effect, Goans had been figuratively castrated over the years and rendered effete. And thus in the course of time, generations of Goans had grown up denationalized (p. 95)."

The above quote doesn't come from any of the characters that abound in the novel. This above statement is inserted in the narrative by the author to remind us about the heinous acts of brutality committed by the Portuguese conquerors on the Goan populace. No historian will ever dispute the atrocities of the Inquisition, nor the ruthlessness by which the Portuguese conquerors put down rebellions, nor Salazar’s brutality in suppressing the genuine Goan aspirations to free themselves from the colonial yoke.

But before the conquest, the most inhuman injustices were seared in into the Goan collective psyche, through their religion and the caste system. In their religion, there was the practice of sati -- burning the widows on the funeral pyre. Afonso de Albuquerque, the Portuguese conqueror of Goa, stopped this barbaric practice. The Devdasi cult, which the author depicts with all its dimensions in the novel, was a part and parcel of that culture.

Dayanand Bandodkar, the first Chief Minister of Liberated Goa, sought to put the Devdasi practice to end a few decades ago. The caste system, in its evil designs, had contucares (the village servants) system and the manducar (serfdom) system incorporated into it. These deep layers of subjugation implanted into the Goan society before the conquest 'pulverized and figuratively castrated' the collective psyche of the Goans.

Being trapped in the immobility of their social structures, the Lusitanian supremacy did not matter to the downtrodden. Their main pressing concern was to eke out a living. The rural uneducated had no luxury of thinking for themselves. Goan journalist Frederick Noronha writes in one of his essays, "a society which has no chance to think for itself is an enslaved society".

Though they were enslaved and servile and branded as denationalized because of the Lusitanian influences that made a way into their soul, they were never de-Goanized. They carried a love for Goa in their soul wherever they went to make a better living; and now in the present, we are the witnesses of Little Goas blossoming in all corners of the world.

The central theme of the novel is expressed through an Australian folk song:

Freedom isn't free You've to pay the price You've to sacrifice For your liberty

Goans were paying the price and making sacrifices to break the chains that bound them. They were imprisoned in Aguada, Peniche, Azores and Africa; and they were brutalized and their liberties were taken away. But Nehru's administration, discarding Gandhi's credo of non-violence, invaded Goa on December 18, 1961, thereby robbing Goans of their right to seize their own freedom from Portuguese colonial rule. One can only hope that the Liberation that was handed to the people on the platter helps them to empower and bring the control of the economy of the land into their own hands.

'Blood and Nemesis' is a thought-provoking novel. The various contradictions that the author introduces through his characters, or his personal comments, in the narrative are debatable issues.

------------------------------------------------------------------- ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Lino Leitao grew up in Salcete, Goa, and was a young man when Goa transitioned out of Portuguese colonial rule. He subsequently migrated to Canada, where he is currently based. Leitao is the author of 'The Gift of the Holy Cross'. His manuscript of short stories is at present being readied for publication. He can be contacted via email at lino.leitao sympatico.ca Goan Observer, which also published this book, earlier printed an abridged version of this review in its issue of August 20, 2005.

GOANET READER welcomes contributions from its readers, by way of essays, reviews, features and think-pieces. We share quality Goa-related writing among the Goanet family of mailing lists. Please do send in your feedback to the writer. Our writers share their writing pro bono. Goanet Reader welcomes your feedback at goanet@goanet.org and is edited by Frederick Noronha fred@bytesforall.org